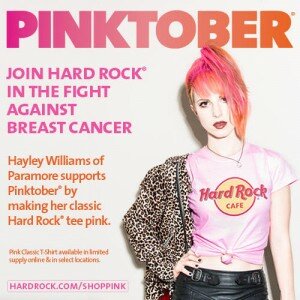

Last week, it was announced that Hayley Williams of Paramore would be the Hard Rock Cafe’s Pinktober ambassador. In conjunction with this, the band is promoting pink Classic Hard Rock t-shirts (in limited supply on their website and at select Hard Rock locations), and donating tickets to their upcoming tour so that breast cancer survivors can attend “The Self-Titled Tour” and meet the band.

In the last week I have been asked to support breast cancer foundations by buying pink Marvelous Moxie lip gloss, go shopping at BJ’s for items like Hershey’s syrup with pink bottle tops, or I could truly indulge by purchasing a pink Ralph Lauren leather bag, where half the $2500 purchase price will go to the company’s Pink Pony Fund.

These are just a sampling of the thousands of ways consumers will be asked to donate to breast cancer charities, and no one will protest. We have come to expect to be awash in pink in October, just as November brings turkeys, and December brings Santa Clause.

But we shouldn’t be so reticent to accept this painting of our landscape. Here’s why.

In an age of information overload, charities have become sophisticated marketers. Those that successfully create a brand—Susan G. Komen or Livestrong, for example—receive the most funding, particularly corporate funding, while simultaneously drawing attention away from smaller and more local charities. These underfunded organizations may be more significant from the perspective of the overall social good. Take the example of Alzheimer’s disease. Baby boomers are aging, and significant resources will be needed in terms of patient care and caregiver support. There is no colorful ribbon for this disease, no way to make it pretty. And without that, there is little or no corporate support. After all, why would marketers wrestle with the reality of a devastating disease when they can sell a glossy pink lipstick or simply slap a pink ribbon on a product package instead? That’s not all. With more marketing and more attention, comes misinformation. Today, because of the ubiquity of pink, women continue to believe that breast cancer is the leading cause of death for women. It’s not. Heart disease is far more deadly: 1 in 3 women will die of heart disease, for breast cancer the statistic is 1 in 31.

Tying products to charities is called cause-related marketing. While this started in the 1980s with the American Express/Statue of Liberty campaign, it is only in the last decade that it has become standard operating procedure for most brand companies. By 2010, 75 percent of brands used cause marketing, and 97 percent of marketers think it is an important strategy. Broad acceptance has been driven by two key events: September 11th, after which consumers increasingly expected corporations to demonstrate good corporate citizenship, and the rise in social media, which enabled people to easily share information about charities with their friends and followers. In addition, charitable tie-ins have moved out of corporate PR and into strategic marketing plans, where they are expected to generate profits, not simply goodwill.

Pink ribbons and breast cancer are not the only campaigns. Products from tampons to telephones have tied their brands to charities related to health, education and the environment, causes that appeal to women who are the primary purchasers of consumer products. Pulling at women’s heartstrings has worked, but cause marketing is so omnipresent that it may become marketing wallpaper—it’s there, but you don’t see it.

For sure, charities need money, and businesses should be good corporate citizens. Rather than marry consumerism to philanthropy, however, companies need to embrace social innovation, a strategy whereby philanthropy and sustainability are built into the corporate structure. For example, Warby Parker sells reasonably priced eyewear and donates in a buy-one-give-in strategy. Participant Media produces positive content—An Inconvenient Truth, The Help and Lincoln, among others—and attaches pro-social outreach. Even Walmart—which rightfully has its critics—has moved in this direction by working with suppliers to reduce packaging, thus significantly reducing environmental impacts.

These are a vast improvement over cause-related marketing campaigns that come with consequences for sponsors and society alike. Campaigns are often in conflict with the work that the company does. In a well-known example, KFC sold pink buckets of chicken—a serious snafu in that fried chicken leads to obesity which is considered a significant risk factor for breast cancer. Additionally, consumers are unaware how much of their money, if any, is going to charity. Corporations have been trying to be more transparent in this regard, but the truth is that if a company caps the amount of money they are donating to a charity (“buy this bracelet and help us donate $50,000 to breast cancer research”) you don’t know when the cap has been reach and if you are contributing to the cause. More important, in the glare of the supermarket and the adrenaline rush of buying a $2500 designer handbag, we lose sight of the sick and the poor and the hungry, and maybe just a bit of our humanity. Finally, cause marketing relieves governments and corporations of their social responsibilities for solving large-scale social problems and puts them squarely on the back of consumers.

Cause marketing offers symptom relief—food for the hungry, money for research—but it obscures core problems. Hunger is in truth an issue of joblessness, for example, and buying lip gloss isn’t going to make that go away.